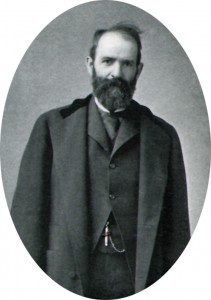

©Google Images

Many historians have regarded Jay Gould as the epitome of a robber baron, based upon a few observations of his actions, without consideration of his understanding of the effects his actions would have upon others. Mr. Gould had an incredible understanding of the business environment that pervaded the American economy after the Civil War. He conducted business by the standards of the time, and is the quintessential American capitalist. As a person outside the business world, he was a devoted family man of exceptional character.

The discussion of Jay Gould will proceed through a logical course. First, I will present a brief biography of Gould, to understand a little of where he came from and what he did. I apologize if this section is slightly “dry” as things will become much interesting thereafter. I do however; believe that it is an essential portion of this analysis. I will then describe who Gould actually was, through his social life, familial and charitable affairs. I will continue by applying what we know of Gould to his business actions that had previously been reported as nefariously self-interested, showing that he was simply conducting business by the standards of the day and often times to the benefit of those in suffering. I will also show that his actions are by all moral standards much more palatable than even events that have recently occurred in American business. Finally, I will make a brief analysis of how Gould’s actions affected the development of America and its economy and present you with some of my own thoughts on conducting the research involved in this production. Citations as well as another author’s recount of Gould will also be provided.

The Life of Jay Gould

Jason “Jay” Gould was born May 27, 1836 to a farming family of New England puritans. As a child, he was small, weak and unimpressive in any area other than his brilliant intellect. While having nothing exceptional in the way of formal schooling, Gould was the archetypal self-educated individual, devoting much of his leisure time to literature. (Alef, 6) He was most interested in mathematics and engineering, which allowed him to take his first position of significance as a surveyor of both his and neighboring counties, a task which included mapping railroad routes.

During the mid-1850’s, Gould entered into his first partnership, joining with Zadock Pratt to construct a tannery. Their business was successful by all accounts until the relationship was terminated when Pratt was unable to decipher Gould’s complex accounting methods – accusing him of using partnership funds for his own gains. No evidence of foul play every surfaced and Gould resolved the dispute by purchasing Pratt’s share. Shortly thereafter, Gould would more to New York City; and, using his knowledge gained in the industry, began operations as a leather merchant and broker. (Alef, 8)

This was to be Gould’s first experience of Wall Street, which would be the stage for many of his legendary performances. The Civil War caused demand for leather goods to be high, as it had many applications to the war efforts. This would enlarge Gould’s coffers to where he could take advantage of the multitude of other opportunities that would arise. His first significant action was to acquire bonds of the Rutland & Washington Railroad at 10 cents on the dollar and consolidate it with the Rensselaer & Saratoga Railroad, which Gould had come to helm with the assistance of his father-in-law Daniel Miller. It was here that Gould learned the intricacies of running a railroad. He would rise to the position of president while also selling the bonds he had purchased at the price of a dime each for $120 each. With these additional funds Gould became more engaged in the buying and selling of stocks and would meet perhaps his most infamous ally: James Fisk.

Gould, Fisk and a temporary partner, Daniel Drew would enter the center stage of the business world when in 1870 they engaged in a battle with Cornelius Vanderbilt (famously known as the Commodore) over the Erie Railroad. As Erie’s treasurer, Drew understood that he could profit handsomely if he were able to retain control of his stock and position with the Erie Company. He sought the assistance of Gould and Fisk, who as brokers, would peddle the shares of stock he had simply printed from the basement of the Erie headquarters. Their buyer, Vanderbilt, was intent upon taking control of the Erie by purchasing an increasing number of shares. Eventually, Vanderbilt realized that he had been purchasing inflated stock and utilized his Supreme Court connections he had Drew and The Erie prohibited from issuing more stock. Throughout this time, the price of Erie stock had skyrocketed. Unwilling to bend to the Commodore, Drew, Fisk and Gould sought their own Judge to place an injunction on the previous order. With these legal tangles in place, they continued printing shares of Erie stock. This all came to an end in 1867 when warrants were issued for the arrest of Drew, Fisk and Gould, who fled to New Jersey. Both sides continued enlisting the service of political figures until Drew decided to end the charade and strike a deal with Vanderbilt. At the time, it appeared as though Fisk and Gould were in the possession of a mountain of debt and a deteriorating railroad. Fortunately for the Erie, investors in Europe were still purchasing Erie shares and the loss was sustainable. Moving forward, Gould anticipated that Drew would attempt to capitalize on the eventual fall of the Erie. Gould knew that Drew had an affinity for the short sale of the stock of failing enterprises. The trap Gould set was ingenious. He utilized his banking connections and a series of certified checks based off of Erie bonds to remove $20 million from the New York money supply. Once Drew had shorted the Erie stock, Gould flooded the street with his currency. The increase in available money caused Erie stock to rise, bankrupting Drew and leaving Gould and Fisk at the helm of the Erie. (Northrup, 58-76)

Now that Gould and Fisk had control of the Erie, they began on their largest endeavor. In 1869, the two gentlemen attempted to corner the gold market. The plan was to acquire large quantities of gold, effectively driving up the market price. As gold was the only accepted medium for international transactions, this would make Midwest farm stores relatively inexpensive to the international markets. To get these goods to the Atlantic, they would utilize the Erie and Gould and Fisk would reap profits. In order to do so, they would need to ensure that the U.S. Treasury would not dump its own gold supply onto the market, which would immediately suppress the price of gold. To achieve this, they enlisted the assistance of Abel Corbin, President Grant’s brother-in-law, by offering to make investments on his behalf. As an added measure, Gould used his influence to have Daniel Butterfield placed as the Assistant Treasurer of the New York Reserve branch. With everything in place, Gould, Fisk and their cadre began purchasing gold. At one point, Gould had invested $25 million, Fisk $60 million. Gold prices steadily rose until President Grant became aware of the situation. Gould was tipped off by Mrs. Corbin and on the day which the Treasury was to release gold onto the market, Gould continued to purchase gold while actually selling more than he was acquiring. Treasury gold hit the market and prices began to plummet, producing widespread panic. Gould again purchased gold once the market had bottomed. At the conclusion of the day known as Black Friday, it is believed that Gould had accrued a profit of $11 million. The amount of profit or loss that he and Fisk would ultimately realize is not known as litigation required them to repudiate much of their contracts and the duo was engaged in legal battles with hundreds of investors for about a decade.

The remainder of Gould’s career was that of acquiring a railroad dynasty by acquiring several of the most important rail systems in the country as well as much of the nation’s telegraph capacity and the New York above ground rail system. Gould first began by capitalizing on the fall of Credit Mobilier scandal, purchasing shares of Union Pacific stock at very low prices. After the Union Pacific president passed away, Gould purchased his stake, gaining a controlling interest in the railroad. By 1879, Gould had gained the Kansas Pacific, Missouri Pacific and Denver Pacific lines. This would place Gould in control of over 10,000 miles of track or 15% of American rail. (Alef, 27,28) Having control of the rails, it made business sense to acquire the accompanying telegraph lines. Using his newspaper, New York World Gould would drive down the stock prices of firms he wished to acquire by printing negative articles about the firm. In this manner he was able to acquire Western Union as well as the Atlantic and Pacific Telegraph companies. Gould had essentially achieved monopoly status in the telegraph industry. It was in this same manner that Gould was able to gain control of the elevated rail system of New York City.

By 1890, Gould was in a deteriorating condition. His works for the remainder of his life would be to place his son George Gould in control of as much of his holdings as possible. Jay Gould would die on December 2, 1892, leaving his fortune of approximately $72 million to be appropriated amongst his family members. (It should be noted that this extremely conservative amount was accepted by the government in an effort to receive the taxes associated with it as quickly as possible.)

© Google Images

Who Was Mr. Gould?

By all accounts, Jay Gould kept to himself. He was secretive and protective of his personal life. He actually kept his personal life entirely separate from his business endeavors – a stark contrast to that of the typical tycoons who relished in the spotlight and were celebrities in their time. In fact, when Gould was not in his office, he was spending his time with his family. He did not belong to any social clubs, nor did he drink or use tobacco. Neither he, nor his wife and children were flashy. They owned the highest quality of everything available yet were not outlandish with their possessions. Interestingly, in personal purchases, Gould would use the same dealers each time he needed to replace an item, never negotiating price or making requests the vendors could not satisfy. Gould did not partake in adventures, finding his pleasures in being with his family and enjoying books and horticulture. Gould actually owned and tended to what was arguably the largest private conservatory in the world, tending to thousands of species of plants, his favorite being orchids of which he owned over 8,000.

An observant stated of Gould: “In his family, he was the best of husbands and I never knew a man who loved his children with such intensity as he did. He seemed to worship them all.” (Northrup, 269) It is perhaps for this reason that Gould held family meetings each morning in which his children would syphon through requests for assistance, choosing legitimate and deserving causes for which to assist through the Gould fortune. Gould was never public with any charitable acts. This is not; however, to state that he was not a charitable man. In fact, his eldest daughter, Helen was to become a philanthropist, most notably furnishing New York University with a library. Gould himself was a proponent of extending the Presbyterian Church. He did this through direct money donations and by providing free passage on his lines to missionaries and pastors. At the request of his sister, he constructed a schoolhouse in Camden. Another educational benefactor was the University of the City of New York. Gould was also known to have given freely to victims of the Chicago fire. As a contribution to America itself, Gould added 80 acres to the grounds of Mount Vernon.

Lyndhurst Mansion, Gould’s Residence ©Google Images

Gould, the Tycoon

In his approach and thoughts regarding business, I believe that Gould can best be summarized through two of his own quotations: “Corporations are going, we are told to destroy the country. But what would this country be but for corporations? Who have developed it? Corporations. Who transact the most marvelous businesses the world has ever seen? Corporations. My theory on investment is this: to go into everything that promises profit. For me business possesses a great fascination. I believe in this country, in its future.” “No man can control Wall street. Wall street is like the Ocean. No man can govern it. It is too vast.” (Northrup, 234,235)

So having reviewed the biography of Mr. Gould, we see that his methods seem quite controlling, while exploiting corruption and the avarice of others. For a reason which I cannot explain, there is an underlying notion amongst our population that business is or should be fair and noble. Business in the days of Gould was ruthless and corrupt, similar to that of today, although its complexities have evolved; the underlying asymmetries are still present. One must only look at the recent scandals of WorldCom and Enron. In each case, setting aside the complex accounting measures that allowed their actions to be relatively concealed and for their actions to be perpetuated on a larger scale, the capability to influence parts of their respective market and thus extract massive amounts of profits for themselves was present. (Stiglitz, 10) These are essentially the same methods that Gould and other tycoons used from 1860-through 1890. In Gould’s day, schemes that were concocted were actually wilder than those of today. One scheme that was proposed against Gould, in 1884, was when a group of brokers conspired to hire a Gould look-a-like for $20,000 to fake Gould’s death to cause his stocks to fall, affording them to make a profit by shorting them. (Northrup, 228) Another example of clever business that occurred in his era is the story of a tussle between Gould and Vanderbilt. After having been undercut by Gould and Fisk, Vanderbilt cut the rate of shipping cattle along his line from $125 to $100. This caused a rate cutting war until Vanderbilt was pleased to see that no cattle were being transported down the Erie line, while his route was filled with cattle at $1 per cart. The commodore was beside himself until he received word that Gould and Fisk had purchased every steer available and shipped them down his very own lines, profiting handsomely. (Northrup, 247)

As it can be seen, the successful businessmen of Gould’s era had a way of thinking “outside the box.” The most popular methods of increasing profits in Gould’s time were by utilizing vertical and horizontal integration in areas of production to maximize profits. Gould recognized that profits could also be increased by increasing demand. It was for this reason that he cornered the gold market. Gould recognized that if the farmers in the Midwest could sell their grain on the global market it would create more volume for his Erie line. He recognized that what is good for others could do him just as well. By manipulating the price of gold, farmers in the Midwest would rejoice and Gould would profit as well. The plan was not as self-interested and narrow sighted as has previously been reported.

Next, we should analyze how Gould expanded his rail empire. Gould always purchased stock in firms that was low. In many cases, he was purchasing lines that were simply dilapidated, having been wrung to the bone of their profits by their previous investors. By making these purchases, consolidating with his existing operations and improving the lines, Gould would return these systems to their profit potentials. Gould understood the operations of railroads to the minutest of engineering details. He took care to personally examine his lines and operations. This all stemmed from his days as a surveyor. By using all of this information, he understood the value and potential of the systems. He used this information to profit. This goes starkly against the notion of a robber baron, or a person who extracts tolls with nothing to return in kind.

Investing in America’s Infrastructure

Railroads were incredibly important in creating a national market. By consolidating, integrating and improving the thousands of miles of rail under his control, Gould was indirectly providing a great service to our country. Conservative estimates give the efficiencies of railroads in 1890 as providing a savings of 5% of GNP, meaning production would have been 5% less per annum in the absence of the rail system. (Miller & Sexton, 161) This may seem like a small amount. When applying this to the rule of 70, we can see that the railroads account for a doubling of the economy in 14 years. This is certainly quite significant, and would have a lasting effect on the economy as a whole as well as on the quality of life people would enjoy.

An area of development in which Gould was a forerunner was in that of the telegraph. Having seen the promise of this invention, he donated liberally to Dr. Morse and his laboratories. Gould created an extensive network of telegraph lines and stations, providing all of America with a means of communication that was incredibly more efficient than anything it previously had access to. Prior to the telegraph, communications could only be received as fast as a horse could travel or over the time it takes to produce and receive a smoke signal. This was an important advance in our society, of which, Gould was the leader.

A final area of consideration is not necessarily in Gould’s actions as a businessman but rather how he and others conspired. They used political corruption and behind the scenes collaboration to form monopolies. In retrospect, it became obvious that these trusts and corporations were in fact corrupt. This eventually led to regulations. The deviously clever minds of Gould and his cohorts presented cases where the government should be involved in business. Prior to this era, there was little if any government involvement in the capitalist world. To the present day, there are still struggles between government regulation and the corporate world. Each time individuals develop a more intricate scheme for profits; oversight is developed to prevent corruption. The start of this whole system began after the Gould era.

Afterthoughts and Commentary

Jay Gould was the quintessential capitalist. He invested his money where he saw opportunity for growth. As we can see through his charitable actions and devotion to his family and faith, he was what would have been an upstanding gentleman. He conducted business in an environment that was ripe with corruption, collusion and deception. I believe that this scenario would be the most extreme example of laissez-faire. Even the government involvement was controlled by the capitalists. Men would go to extraordinary lengths in the name of profit. Gould’s chief competition came in the form of the legendary Vanderbilt himself. Gould’s results speak for themselves. He rose from a modest farm boy to become one of the greatest tycoons our country would know. He used his intellect and clever wit to find and provide himself with opportunities for profit. He saw the world of business as a great marvel, providing him with thrills and great wealth. While many have criticized Gould’s methods, they were no different from that of any other man at the time. My personal opinion is that Gould was actually a victim of his own character. I believe that because Gould was not large, boisterous and outgoing like the other tycoons, he was received much differently. His being withdrawn caused him to be seen more as a scoundrel. While the other tycoons were at social gatherings, garnering attention and basking in their fame, Gould was not. He did not desire the celebrity status that would have accompanied his fortune, as was common for the time. This would cause the perception of him to be different from that of his fellows. It is also my opinion that had he not attempted to corner a market so large and important as the gold market, which is a commodity tracked by virtually everybody, the scandal may have not tarnished his name to the amount that it did. Few people know of the railroad and telegraph empire that Gould had built. When his name is spoken; however, Black Friday and the attempted corner of the gold market immediately come to mind.

Taken as a whole, Jay Gould was an incredibly diligent man who successfully ascended to the precipice of the business world. He played by the rules of his day and was one of the greatest players. He was a man who respected and believed in the American economy. The results of his actions set the stage for our nation to experience prosperity unlike any global power would ever know. I have no doubt that had he lived during the modern era, he would have used his intelligence and creativity to rise to success, playing by the more ethical standards of today.

Conducting research on the life of Mr. Gould was a rather enjoyable experience. I was able to review literature spanning over a century and saw a pattern of change in how Mr. Gould was perceived. The earliest dated text concerning Gould was that of Northrup, published in 1892 (the year of his death). This text was a rather large collection of various stories as well as personal accounts and comments, combined with excerpts from other publications and congressional hearings. It presented a stark contrast between Gould’s business and family lives. A reader who only received the information regarding Gould’s business endeavors would lead a mob to have the man burned at the stake. One who read only that of his personal affairs would place him among the ranks of Mother Theresa. Although lengthy, this was actually the most engaging of the texts I studied, as it included hundreds of personal accounts and observations that were lacking in the other texts.

Through my studies, I noticed a trend in how the perception of Gould by the authors would change as time passed. As time has progressed, Gould is portrayed less as a villain and even to the degree that he is acknowledged as a founder of the greatest economy the world has known. My take on this is that with time, we have been able to analyze more information as well as see the full effects of his actions. Did history change? No; but, how we relate to it does. This is perhaps one of the greatest takeaways one can have from this analysis.

Please follow the following link to watch Edward Renehan review his work on Jay Gould with CSPAN.

http://www.c-spanvideo.org/clip/4177025

Sources Used

Alef, Daniel. Jay Gould: Ruthless Railroad Tycoon. Santa Barbara: Titans of Fortune, 2010. Print.

Josephson, Matthew. The Robber Barons. Orlando: Harvest Book, 1962. Print.

Klein, Maury. The Life and Legend of Jay Gould. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1986. Print.

Miller, Roger L. and Sexton, Robert L. Issues in American Economic History. Mason: South-Western, 2005. Print.

Morris, Charles R. The Tycoons: How Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould and J.P. Morgan Invented the American Supereconomy. New York: Owl Books, 2005. Print.

Northrup, Henry D. Life and Achievements of Jay Gould. Philadelphia: Southard Publishing Co., 1892. Digital Print Copy.

Renehan, Edward. “The Dark Genius of Wall Street: Jay Gould.” CSPAN Video. Web Video. 29 Nov. 2012. < http://www.c-spanvideo.org/program/187719-1>

Stiglitz, Joseph E. The Roaring Nineties. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2003. Print.

“Jay Gould.” Wikipedia. Web. 29 Nov. 2012. < http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jay_Gould>

“Jay Gould.” The Biography Channel. Web. 29 Nov. 2012. <http://www.biography.com/people/jay-gould-9316806>

“Jay Gould.” Famous People. Web. 29 Nov. 2012. < http://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/jay-gould-240.php>

Images secured from Google Images.

Download this page in PDF format

Download this page in PDF format