Note: Again, the Sage American History website/text, like most history texts, devotes most of it’s discussion of the post WWII era to discussions of politics and foreign affairs, especially wars. We are more interested in economic developments and so I have skipped some of the material and excerpted the following.

Post-World War II Domestic Issues

The Truman-Eisenhower-Kennedy Years

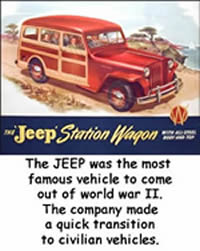

Post World War II America saw changes in everyday life scarcely imaginable in the 1930s. The military requirements of war had generated enormous advances in technology, medicine, communications and the implements of war. Medicines such as penicillin, antibiotics and techniques for the treating of injuries and diseases were greatly stimulated by the demands of warfare and its impact upon civilian populations. The research that went into the development of the atomic bomb also produced information about the phenomenon of radiation and how it applied to such things as x-ray technology. The first jet aircraft were developed by Germany during the Second World War, and all-purpose vehicles such as the famous Jeep (general purpose vehicle) fostered advances in automotive design. Radar and other sophisticated technology devices had uses that would later be applicable in the civilian arena for civil air control. Methods developed by companies such as Kaiser advanced the technology necessary for building ships of all sorts. The Kaiser-Permanente health plan was created by that corporation in the World War Two era.

As typified by the mythical figure of Rosie the Riveter, the roles of American women had changed dramatically during the world war. Approximately 800,000 women served in the Armed Forces in a variety of capacities. For the 13 million men who served, the military experience was also eye opening: farm boys, city dwellers, college students, businessmen, teachers, musicians, artists, laborers and skilled technicians serving together—not to mention an unparalleled mixing of racial and ethnic groups, and men from different geographic areas—brought new perspectives to the men who served in the armed forces during the World War II era.

The difficulty was that when those men returned, they had changed, often drastically, and so had the women they had left behind. The younger soldiers and sailors had gone off as boys of 18 and returned as old men of 21. The girls had gone to work in factories, businesses, USOs and Red Cross or other patriotic agencies and were now independent-minded women, not necessarily ready to resume the status quo. The end of the war was indeed a time for celebration, and the returning GIs were treated as heroes. But getting back to a “normal” life was difficult. Many men and women who had married during whirlwind courtships of weeks or even days before the men left discovered that their spouses were strangers; the person they remembered had changed. The result of all these changes was that marriage, birth and divorce rates all rose dramatically in the postwar years.

Domestic Issues and the Cold War. Nothing happens in a vacuum in the real world. In post-World War II America, Cold War issues and domestic issues overlapped significantly. As citizens of the most powerful nation in the world, the people of the United States were not ready to reembrace the posture of prewar isolationism; indeed, most Americans probably felt that the United States had a responsibility to help order things in the rest of the world. Programs like the Marshall Plan, which provided massive economic aid to the recovery of the devastated nations of Europe, was a measure of that sense of responsibility. The development of the interstate highway system, a project that had an enormous effects on the domestic lives of Americans, was nevertheless justified in part by national security needs. The space race, which began with the launching of the Soviet satellite Sputnik, might be viewed as a domestic initiative. Yet part of the motivation for the massive effort to conquer space was clearly the fact that, as one political figure put it, “I do not want to sleep at night under the light of a Russian moon.”

The civil rights movement was perhaps the most significant and important domestic development in post-World War II America, at least until the end of the 20th century. Yet even that issue was propelled to a certain extent by concerns about how segregation in American society might be used against us in the competition among nations. It was difficult for Amerficans to point fingers at nations that ruled their citizens with an iron fist while millions of Americans lacked full freedom at home.

Economic issues certainly resonated with respect to the international position of America. President Eisenhower’s warning in his farewell address of the “military-industrial complex” illustrated the fact that our industries, and the research being down in our universities, were focused heavily on the development of weapons and tools for the waging of war. American movies and television, created primarily for domestic consumption, nevertheless provided a window on American society to the rest of the world, and that view did not always portray America in a favorable light. Indeed, one recent Secretary of Defense pointed out that a certain American international spy drama might well have unfortunate propaganda uses for America’s enemies.

The treatment of Cold War issues and domestic issues will, therefore, require some back-and-forth. Where appropriate, links will be provided to issues that straddle historic events in both the international and domestic arenas.

The Postwar Economy. Another thing that was obviously true after the war was that the Depression was over. Massive government spending during the war—twice as much as in all of America’s prior history combined—had ended unemployment and created tens of thousands of new jobs for men and women. Dust bowl farmers who had arrived in California destitute in the 1930s had found jobs in aircraft and ship building plants and were well off by 1943. Soldiers with families sent their paychecks home; there was little to spend them on in many places where they were stationed. Instead those paychecks went into savings accounts because their wives were working and also had little on which to spend the extra income: no appliances, no new cars, and very few luxury items, for industry had devoted its full attention to the war effort.

The post-war era was a time of economic boom. Soldiers returned with hundreds of dollars in back pay, and wives who had been working had been able to save because there were few luxuries on which to spend income. Many consumer products had been mostly unavailable; companies that had made appliances had been building the implements of war. American labor had prospered; by 1945 union membership was at almost 15 million, over 35% of the nonagricultural labor force, an all-time high. In 1946 President Truman recommended measures to Congress designed to help the economy recover. With the huge demand for consumer goods and new homes, anti-inflation measures were instituted to keep the overheating economy under control. Life did not return to what it had been in 1940—it took off in exciting and often confusing new directions.

Fears that the returning GIs would cause economic hardships did not materialize, for the need to shift the economy back to peacetime production demanded a lot of labor. Although local conflicts occurred over hiring priorities and preferences for veterans, there was plenty of work to go around. Americans spent, but not wildly, for memories of the Depression returned as those of the war began to fade. Though the economy boomed, it did not get out of control, and fear of another depression gradually waned. The postwar agonies historically faced by many nations—rampant inflation, rioting, labor disorders—were not completely absent in the U.S. from 1945-1955, but they did not rise above manageable proportions. For one thing, the demands of the Cold War and other factors kept government spending at high levels, and the demand for consumer goods and new homes kept the economy moving upward. Americans had never had it so good. They knew it and were proud, feeling they had earned it.

The Truman Years, 1945-1950

One of the great American films of all time, “The Best Years of Our Lives” (1947), explores the readjustments that had to be made by returning veterans. The ex-Army master sergeant who goes back to his position as a banker views loan applications from his fellow ex-servicemen very differently from the bank officials who had stayed behind. The sailor who  returns with metal hooks instead of the hands he lost in a shipboard fire discovers that his family has even more trouble adjusting to his injury than he had in adjusting to the mechanical devices. The former Army Air Corps bomber pilot discovers that the skills required in leading 10 men in a complex machine over enemy territory do not translate readily into the postwar workplace. He also discovers that his bride, whom he had known for only days before his departure, is a total stranger; he can’t wait to get out of uniform, but she wants to parade him around in it to show him off to her friends.

returns with metal hooks instead of the hands he lost in a shipboard fire discovers that his family has even more trouble adjusting to his injury than he had in adjusting to the mechanical devices. The former Army Air Corps bomber pilot discovers that the skills required in leading 10 men in a complex machine over enemy territory do not translate readily into the postwar workplace. He also discovers that his bride, whom he had known for only days before his departure, is a total stranger; he can’t wait to get out of uniform, but she wants to parade him around in it to show him off to her friends.

The Best Years of Our Lives, directed by William Wyler, starred Fredric March, Myrna Loy, and Dana Andrews. Harold Russell played the part of a sailor who had lost his hands. The film won 7 Academy Awards, including a special Oscar for Harold Russell, whose handicap was real.

I was nine years old when the war ended, but the memories remain vivid. My best friend and I each lost a brother. In the village of Pleasantville, New York, where I lived, every year on Memorial Day a parade began and ended at the village plaza near the railroad station. A scroll of honor had been erected there with the names of all the young men from Pleasantville who had served in the war. Next to the name of each one killed was a gold star. As part of the ceremony ending the parade, the names of all those who had died were read over a loudspeaker. While I do not recall the names or numbers, I remember vividly the weeping of many of the people in the crowd, for everyone in the village knew at least one person who had been killed.

Looking back, it is hard to imagine how many things we now take for granted were different in 1945. To mail a first-class letter cost three cents; air mail was extra. Practically no homes had a television set; even by 1949 less than 3% of residences had one. There were no pushbutton or dial telephones; you would pick up the receiver and wait until an operator, inevitably female, said, “Number, please?”—and you gave her the number. You had to ask for a special operator for long-distance. A significant percentage of farm homes were still without electricity or indoor plumbing; appliances such as refrigerators and washing machines and dryers were luxuries which many working-class families could not yet afford.

As virtually no automobiles had been manufactured from 1943 to 1945 because the auto companies were busy building tanks, jeeps, 5-ton trucks and military aircraft, the old 1940 and 41 models were brought out again until designs could be revamped. The Singer company went back to making sewing machines instead of machine guns, and silk was once again used for stockings instead of parachutes. Butter, sugar, meat and gasoline were no longer rationed. People took their old cars down off the blocks where they had sat during the war because of tire and gasoline rationing, and the top half of headlights no longer had to be painted black for air defense.

The Housing Boom. The critical need for the returning men starting families was housing. University campuses provide an interesting glimpse of how different effects of the war came together. The GI Bill of Rights, which included provisions for college tuition assistance, as well as job training and help with home loans, helped create a new phenomenon. Veterans who might never have thought about going to college decided that it was worth a try, since Uncle Sam was footing part of the bill. Men who chose to attend college on the GI Bill did not necessarily delay marriage, as they had postponed their lives long enough while at war. They often delayed having children so that their wives could work, but they were still families, and around the fringes of college campuses makeshift structures such as tin Quonset huts, old military barracks or other temporary buildings were converted into cheap apartments. The married college student—until 1945 an oddity for the most part—was now a fixture on the campus.

Elsewhere the demand for housing was equally strong, and thousands of young families were willing to move into new suburban communities such as Levittown, Long Island, (left) where prefabricated houses were constructed from one set of plans in row after row, even to the placing of a single tree in the same place in every yard. Some social critics found such communities appalling in their sameness. But the occupants, who perhaps remembered growing up in the Depression 1930s, found that paint, do-it-yourself landscaping and other improvements could create some sense of personal identity. All the same, cartoonists and song writers had fun with this “ticky-tacky” life style.

|

|

|

One extra that did not come with suburban houses but which was often indispensable to this new suburban way of life was the automobile. In the immediate postwar years, Ford, GM, Chrysler, Kaiser, Studebaker, Hudson, Packard and the other manufacturers retooled their plants from making trucks, tanks and jeeps. They dusted off prewar designs and began producing cars that looked very much like 1939 and 1940 models. But within two or three years newer, sleeker, more streamlined and modern designs appeared, and the automobile age took off. Cars and gasoline were cheap—in fact the gas war became a roadside feature in the 1950s, as did the drive-in restaurant with curbside service, the drive-in movie theater, and a new form of temporary lodging, the motel. At first few new cars had air-conditioning, fancy radios or automatic transmissions, which through the 1950s were often expensive extras. But they were bright, shiny and colorful, and when the interstate highway system was begun under President Eisenhower in the 1950s, they would take you almost anywhere in unprecedented comfort and speed.

American labor had also prospered during World War II. By 1945 union membership was at almost 15 million, over 35% of the nonagricultural labor force, an all-time high. In 1946 President Truman recommended measures to Congress designed to help the economy recover. With the huge demand for consumer goods and new homes, anti-inflation measures were instituted to keep the overheating economy under control. This attempt was made despite the fact that the Office of Price Administration, which had kept a lid on inflation during the war, was abolished in 1947. Life did not return to what it had been in 1940, it took off in exciting and often confusing new directions.

American labor had also prospered during World War II. By 1945 union membership was at almost 15 million, over 35% of the nonagricultural labor force, an all-time high. In 1946 President Truman recommended measures to Congress designed to help the economy recover. With the huge demand for consumer goods and new homes, anti-inflation measures were instituted to keep the overheating economy under control. This attempt was made despite the fact that the Office of Price Administration, which had kept a lid on inflation during the war, was abolished in 1947. Life did not return to what it had been in 1940, it took off in exciting and often confusing new directions.

As Franklin Roosevelt’s successor, President Harry Truman faced enormous challenges. Truman had not even wanted to be vice president, and when he received the shocking news of the president’s death from Eleanor Roosevelt at the White House, his first words were, “Mrs. Roosevelt what can we do for you?” Maintaining her composure, the president’s widow answered, “No, Harry, what can we do for you? For you are the one in trouble now.”

Truman initially promised to carry on with Franklin Roosevelt’s policies, but he eventually designed his own legislative program. Although President Truman did succeed in overseeing a reasonably orderly transition to a healthy peacetime economy, his ambitious political program ran into difficulty with the Republican Congress elected in 1946. Opponents of Roosevelt’s New Deal had used the war to get rid of many of Roosevelt’s measures, and conservative Democrats and Republicans were not prepared for a second new deal.

By 1947 the Armed Forces had been reduced to a size of 1.5 million, and the discharged veterans were eager to take advantage of the GI Bill. Veterans were entitled to financial support for education and vocational training, medical treatment, unemployment and loans for building houses or starting businesses. They were eager to marry and start families, and by 1946 the well-known baby-boom was underway; the birth rate in 1946 was 20% higher than in 1940 and continued at a high rate until the 1960s.

President Truman made significant advances in the area of civil rights. Because Congress was not prepared for major civil rights legislation, President Truman used the power of his office to desegregate the Armed Forces and forbid racial segregation in government employment. (See Executive Order 9981, Appendix.)

With a strong labor flexing its muscle, and with the huge demand for consumer goods, the American economy was vibrant. But workers were in a position to make demands, and they did. President Truman was at the center of the struggle between labor and management, and in order to strengthen his position with labor, a natural Democratic constituency, he vetoed the controversial Taft-Hartley Act of 1947. It was called by some the “slave labor act” because it was seen as unfriendly to labor and unions. Truman’s veto was overridden, and the act banned the closed shop (union only shop.) It also prohibited union contributions to political campaigns, required union leaders to swear that they were not Communists, and included other stern measures.

Despite conflict between President Truman and the Republican Congress, much was accomplished in the postwar years. The National Security Act of 1947 revised the Armed Forces, creating the Department of Defense, a separate United States Air Force and the new National Security Council. In addition the law made the Joint Chiefs of Staff a permanent entity and established the Central Intelligence Agency, an outgrowth of the wartime Office of Strategic Services, or OSS, to coordinate intelligence gathering activity. In 1951, in a reaction against the extended term of Franklin Roosevelt, Congress passed and the states ratified the 22nd Amendment, which limited all presidents after Truman to two terms.

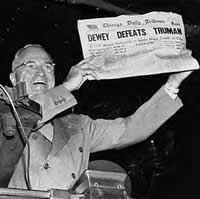

The 1948 Election. The 1948 presidential election was one of the most memorable in American history. The Republican candidate, Governor Thomas Dewey of New York, had gained fame for his anti-crime work and had run against Roosevelt in 1944. Because of Harry Truman’s support for civil rights, including the integration of the Armed Forces and the United States Civil Service, a number of Southern Democrats left the Democratic Party. They nominated South Carolina Governor J. Strom Thurmond on a States’ Rights Democratic ticket; they were called the “Dixiecrats.” Meanwhile the left wing of the Democratic Party nominated Henry A. Wallace on a Progressive Party ticket. Those two defections from the Democratic ranks seemed to doom President Truman’s chances for reelection.

By mid-September the polls were predicting a sure victory for Governor Dewey, and taking the polls seriously Dewey conducted a lethargic campaign, assuming that he had the election in hand. President Truman, however, went on a whistle-stop campaign by train in which he covered 31,000 miles and made speeches all along the way. He criticized the “do-nothing Congress,” and people in the audience yelled, “Give ’em hell, Harry!” The President responded, “I don’t give them hell—I just tell the truth and they think it’s hell!” His supporters would roar with laughter and applause. Post-election analyses later showed that Truman was closing the gap rapidly in the last few days before the election. Without the assistance of modern computers, however, the pollsters were unable to keep up with the changes. Thus on election night everyone still assumed that Governor Dewey could rest easy.

By mid-September the polls were predicting a sure victory for Governor Dewey, and taking the polls seriously Dewey conducted a lethargic campaign, assuming that he had the election in hand. President Truman, however, went on a whistle-stop campaign by train in which he covered 31,000 miles and made speeches all along the way. He criticized the “do-nothing Congress,” and people in the audience yelled, “Give ’em hell, Harry!” The President responded, “I don’t give them hell—I just tell the truth and they think it’s hell!” His supporters would roar with laughter and applause. Post-election analyses later showed that Truman was closing the gap rapidly in the last few days before the election. Without the assistance of modern computers, however, the pollsters were unable to keep up with the changes. Thus on election night everyone still assumed that Governor Dewey could rest easy.

In one of the most famous journalistic gaffes in American political history, the Chicago Tribune came out with its famous headline, “Dewey defeats Truman.” The next morning a victorious Harry Truman held up the paper grinning broadly—he had won 49% of the vote and had achieved a 303 to 189 margin in the Electoral College. Harry Truman had won his second term and was president in his own right. The blunt, plain-spoken Missourian, who had a famous sign on his desk—“The Buck Stops Here”—would serve four more years.

In 1949, President Truman, inspired by his stunning upset victory in the election, introduced a new legislative agenda, which he called the “Fair Deal.” It sought to take up where the New Deal had left off and included repeal of the Taft-Hartley Act, raising the minimum wage and expanding social security. Conservatives, however, feeling that they had seen government programs advance more than far enough under Roosevelt, gave lukewarm support at best to Truman’s ideas, although some bills were passed. Congress had also passed the 22nd Amendment, which was ratified in 1951. Although it did not apply to President Truman, his election in 1948 was the fifth straight Democratic victory. Had he chosen to run again in 1952, he probably would have met the same fate as Adlai Stevenson, who lost in a landslide to World War II hero General Dwight Eisenhower.

For more on the political career of Harry Truman see David McCullough, Truman (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992) and Harry S Truman, Memoirs of Harry S. Truman: 1945 Year of Decisions (New York: Doubleday, 1955) & Years of Trial and Hope, 1946-1952 (New York: Doubleday, 1956). See alsoTruman (1995), starring Gary Sinise & Diana Scarwid, directed by Frank Pierson, based on McCullough’s book.

The 1950s: The Eisenhower Years

The 1950s were a decade of both stability and change. Inflation was tamed even as the economy continued to grow; for example government workers and military personnel received no pay raises from 1955 to 1963 because inflation remained at near zero. The civil rights revolution in the South got started in 1954 and 55 with the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka and the Montgomery bus boycott begun by the courageous Rosa Parks. For most of middle America, however, the 1950s were a time of flashier cars, the expansion of television, the rise of rock ‘n roll, mass production, the accelerated movement to suburbia, and a rising but strangely dissatisfied middle class. Underneath the somewhat tranquil exterior of American society the beat generation brought a foretaste of the rebellious 1960s.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected president in 1952. He was nominated over conservative Senator Robert Taft of Ohio following a lively contest at the Republican convention. He selected as his vice president Senator Richard Nixon of California. By election day it was clear that everyone liked Ike, and he was elected in a landslide. Eisenhower was better prepared for the Presidency than many imagined, for in his job as Supreme Allied Commander in Europe during the war he had had to deal with both political and military matters. But that experience did not quite prepare him for all the political machinations of Washington. (See Dwight D. Eisenhower, Crusade in Europe, New York: Doubleday, 1949.)

Along with the civil rights turmoil in the South that increased during the 1950s, an undercurrent of fear and anxiety persisted because of the nuclear arms race. With the growing threat from the Soviet Union, the military was enlarged, and military spending helped stimulate the economy. One project begun by President Eisenhower as a national defense measure was the creation of the interstate highway system. Within a decade Americans could drive almost literally from coast to coast without encountering a stop light. American life became ever more focused on the automobile. Although a significant number of families still did not own a car, and few families had two cars, the automobile had become a necessity rather than a luxury for most Americans.

By the mid 1950s the Depression years seemed far away. Most Americans were enjoying a standard of living that was unprecedented. Not all of the economic news was good, however. Americans had benefited in the immediate postwar years because their industrial facilities had been untouched by the war. But as the European nations built new factories to replace the ones that had been bombed out, American industries faced obsolescence. As farming methods continued to improve, farmers were able to produce more and more, driving the prices of agricultural goods down. The federal government initiated various price supports to prop up farm commodities. The struggles of American farmers never seemed to cease, from the Populist era through the twenties and the Depression and into the late 20th century.

Suburban life centered around the family, and most Americans felt that life was pretty good. However, an undercurrent of frustration persisted. One tale about the apparent sameness of the suburbs had a man getting off his commuter train, walking absently toward his home, accidentally walking a block too far, entering a house that seemed to be just like his own, to be greeted by a wife who seemed familiar. Only after the couple had sat down to dinner and started to talk did everyone realize that the man had arrived at the wrong house. Sloan Wilson’s novel, The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit, and the film of the same name starring Gregory Peck reveal the pressures of 1950s conformity and the haunting memories of the Second World War. Although the modern feminist movement had not yet begun, its seeds were being planted among bright, educated women who were finding that being a housewife and mother were not always fulfilling. (The recent AMC TV series Mad Men covers the same era and has won awards for historic authenticity.)

Although he had suffered a heart attack in 1955, President Eisenhower felt fit and competent to run for reelection in 1956, and he won by another landslide. Recognizing that that many people still “liked Ike,” the Democrats decided to stay with their 1952 candidate, Governor Adlai Stevenson. The rather dull Democratic convention suddenly came to life when Stevenson announced that he would not designate his own candidate for vice president, but opened the nomination to the convention. A lively contest ensued, pitting Senator Estes Kefauver and others against the young Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts. Although Kefauver won, Kennedy made a very graceful concession speech, which Democrats in 1960 obviously remembered.

For all the subliminal discontent, Americans were generally self-assured and confident in their ability to meet life challenges, both domestic and international. That certitude was ruptured, however, with the startling announcement in 1957 that the Soviet Union had launched the first orbital satellite. It was called Sputnik. While fascinating to scientists, the Russian satellite struck fear in the hearts of many who believed that the Soviets would convert their successes in outer space into military advantage. Before the United States could get its first satellite aloft, the Russians had sent a cosmonaut, Yuri Gagarin, into orbit. While Soviet rockets seemed capable of sending large payloads into space, American rockets often blew up on the launch pad. It was not until President Kennedy announced a national goal of landing an astronaut on the moon and returning him safely to Earth before the end of the decade of the 1960s that America began closing the gap in the space race.

In reaction to the launching of Sputnik Congress passed a bill creating the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and another, the National Defense Education Act, to improve American education by beefing up programs in mathematics and science. While Americans continued to like and respect President Eisenhower, he seemed like a grandfather figure to many. By the time of the election of 1960, Americans sought a younger more vigorous president, whom they got in John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

Life in the 1950s in America had about it rather glaring inconsistencies. On the surface, much seemed well. People were making more money than ever before; men and women were going to college in far greater numbers than ever before; television was a new form of entertainment, which by the mid-1950s was a feature of a majority of households, though most households had only one small black-and-white set (left). Sports were more popular than ever, popular music was going off in new directions with the emergence of Elvis Presley and rock and roll, and industries like aircraft changed people’s transportation habits almost as much as the train or automobile. The St. Lawrence Seaway connecting the Great Lakes with the Atlantic Ocean was also opened in 1959. Ceremonies in Chicago and elsewhere were attended by President Eisenhower and Queen Elizabeth II. Nostalgic films have shown the 1950s to be good, comfortable, at least, and free from turmoil, although some might say they were bland and often uninteresting, maybe even boring. But overall, the “nifty fifties” were still good.

But there were dark sides. In the South, and in parts of the North as well, racial tensions that had been smoldering since Reconstruction began to emerge with the birth of the modern civil rights movement. And while the world was relatively at peace, various crises in Europe, Asia and the Middle East kept tensions high. And above all-there was the bomb. Until 1949 the U.S. was the only nation that had produced (and used) atomic weapons. When Soviet Union scientists, whom many believe were aided by secrets stolen from the U.S., exploded its first atomic device, the atomic (later nuclear) arms race was on.

The two superpowers established what became known as the balance of terror as more and more powerful weapons were produced and tested. School children were drilled on what to do in case of a nuclear attack, subterranean bomb shelters were built (sometimes in people’s back yards), and for a long time the assumption was that sooner or later World War III—more horrible than World Wars I and II put together—was bound to start. One did not have to be a pessimist to think the unthinkable, that it was not a matter of “if,” but “when.” It was for understandable reasons that the Cold War was also known as the balance of terror.

The Kennedy Years

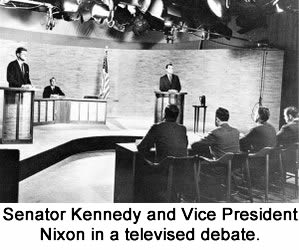

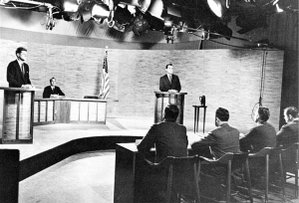

The 1960 election was a milestone in terms of the impact of television on electoral politics. Richard Nixon, who had been vice president under President Eisenhower for eight years, and who had a number of notable achievements on his record, was a formidable, intelligent candidate with broad experience and a sophisticated understanding of foreign affairs. Although he received only lukewarm support from the outgoing president, Richard Nixon was not to be taken lightly.

The 1960 election was a milestone in terms of the impact of television on electoral politics. Richard Nixon, who had been vice president under President Eisenhower for eight years, and who had a number of notable achievements on his record, was a formidable, intelligent candidate with broad experience and a sophisticated understanding of foreign affairs. Although he received only lukewarm support from the outgoing president, Richard Nixon was not to be taken lightly.

Senator Kennedy of Massachusetts, on the other hand, had many visible assets, including a charming young wife and family, a Harvard education, a record of heroism in World War II, and the backing of a wealthy and powerful family. Yet his years in Congress and the Senate had been undistinguished, and when Adlai Stevenson opened the nomination for vice president during the 1956 Democratic convention, Kennedy lost his bid to Estes Kefauver. Kennedy also had to reckon with the fact that he was attempting to become the first elected Irish Catholic president in American history. If he won, he would also be the youngest man ever elected president of the United States.

In retrospect the outcome of the election and seems to have turned on the first televised debate between Senator Kennedy and Vice President Nixon. Kennedy’s movie star good looks and smooth performance overshadowed the haggard, pale appearance of Richard Nixon, who had recently been hospitalized, and who looked far less appealing to the television audience, having declined to use makeup. Those who heard the debate on the radio and did not see it divided their sentiments regarding the winner 50-50 between the two candidates. For those who saw the debate on television, Kennedy came out ahead by a substantial margin. The vote was one of the closest in American history; Kennedy’s margin was 118,000 votes out of 68 million cast.

The 1960 election was also notable in that for the first time, citizens in Hawaii and Alaska were able to vote in a presidential election; both had become states in 1959.

Probably because of his assassination and the nonstop television coverage of all of events during the weekend leading up to the funeral, including the heroic performance by Jacqueline Kennedy and the tragic image of the her two young children saying farewell to their father on camera, Kennedy’s popularity was probably even greater after his death than during his administration, and people without a deep knowledge of politics considered him to have been a great president. In fact, Kennedy’s domestic record was quite modest. He was unable to persuade Congress to follow his lead in a number of his initiatives, and most of his proposals, especially in the civil rights area, were finally realized under the powerful Lyndon Johnson, who succeeded Kennedy after his death. Congress did support Kennedy’s creation of the Peace Corps and passed economic programs for urban renewal, raising the minimum wage, and increasing Social Security benefits. Critics have claimed that Kennedy’s performance in office had more style than substance, but there is no question that the White House seemed a far more glamorous place with the Kennedy family in residence. There is also little doubt that his handling of the Cuban missile crisis was his finest hour.

Probably because of his assassination and the nonstop television coverage of all of events during the weekend leading up to the funeral, including the heroic performance by Jacqueline Kennedy and the tragic image of the her two young children saying farewell to their father on camera, Kennedy’s popularity was probably even greater after his death than during his administration, and people without a deep knowledge of politics considered him to have been a great president. In fact, Kennedy’s domestic record was quite modest. He was unable to persuade Congress to follow his lead in a number of his initiatives, and most of his proposals, especially in the civil rights area, were finally realized under the powerful Lyndon Johnson, who succeeded Kennedy after his death. Congress did support Kennedy’s creation of the Peace Corps and passed economic programs for urban renewal, raising the minimum wage, and increasing Social Security benefits. Critics have claimed that Kennedy’s performance in office had more style than substance, but there is no question that the White House seemed a far more glamorous place with the Kennedy family in residence. There is also little doubt that his handling of the Cuban missile crisis was his finest hour.

See also Cold War.

The question still discussed about President Kennedy’s foreign policy—one for which there is no satisfactory answer—is: “What would Kennedy have done in Vietnam if he had not been assassinated?” Some believe that he was prepared to end what he saw as a misguided venture; however, advisers close to the Kennedy administration have indicated that if his intent was to begin a full withdrawal from Vietnam, they had seen little evidence that he would carry it further. True, he had drawn down the number of advisers in Vietnam slightly during the last months of his presidency, but some believe that that was just preparation for the election of 1964.

In the end, Kennedy followed the path of Presidents Truman and Eisenhower as a leader determined to prevent the further spread of Communism in the world and to use all reasonable means to keep the Soviet Union from taking advantage of any perceived American weakness. He had campaigned on the issue of a missile gap between United States and the Soviet Union, and even his plan to place a man on the moon in the decade of the 1960s was, to a large extent, aimed at defeating the Russians in space. The military implications were obvious. It was, of course, during Kennedy’s administration that the most dangerous point in the Cold War was reached: the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962.

The Space Race. During the mid 1950s most Americans were aware that the government was doing research on the exploration of space and that one day, probably in the far distant future, men would go to the moon and beyond. But when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, an artificial satellite, into Earth orbit in 1957, Americans were stunned. Russian scientists had been portrayed as less capable than their American counterparts, and Soviet successes were supposedly based on borrowing of western ideas. But when the Soviets leaped out in front in space exploration, even with a primitive vehicle, Americans reacted with a combination of disbelief and panic. Articles with titles like “Why Johnny Can’t read-And Why Ivan Can” began to appear, and the entire U.S. educational system was hauled into court and placed under scrutiny. Reflecting people’s attitudes, Congress passed legislation that created the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and passed additional laws meant to improve American science and math curricula. The space race was seen as part of the cold war, and Americans felt they had to win.

No one played this theme more strongly than President Kennedy. Early in his administration he dedicated that nation to putting a man on the moon and returning him safely by the end of the decade, defined as January 1, 1970. The seven Mercury astronauts made flights in the early 1960s, and then the Gemini and Apollo programs began to prepare for an eventual lunar landing. With the assistance of former German V-weapon rocket scientists and an aviation industry with much talent, the Americans caught up with and passed the Soviets and reached Kennedy’s goal: Astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the moon in July, 1969.

NASA eventually oversaw six landings on the moon, the last one on December 11, 1972. Since then all space flights have been limited to low orbits. The Space Shuttle program, which followed Apollo, accomplished much but was plagued by accidents, as the Challenger shuttle was destroyed during a launch in 1986, and the Columbia was destroyed during re-entry to the Earth’s atmosphere in 2003. NASA plans to retire the remaining shuttle craft in 2010 and replace them with a new vehicle, the Orion, designed to take astronauts back to the moon and perhaps beyond.

See Tom Wolfe, The Right Stuff and the film of the same title; Norman Mailer, Of A Fire on the Moon; Also dramatic and historically sound are the Tom Hanks film Apollo 13 and his HBO series, From the Earth to the Moon. The NASA web site is one of the most popular and frequently visited on the World Wide Web.

Post-World War II Domestic Part 2

The Johnson and Nixon Years

The Johnson Years: America in Turmoil

Lyndon Baines Johnson was one of the most fascinating and controversial figures in American political history. He was a man of extraordinary talents, appetites and ambition. He first came Washington from Texas in 1931 as secretary to a Texas congressman, where he caught the attention of Franklin Roosevelt and was appointed as Director of the Texas National Youth Administration. He was elected to a full term in the House of Representatives in 1938 and served there until 1948, when he was elected to the United States Senate.

In 1951 Johnson was elected majority whip of the Democratic Party in the Senate, and in 1955 he became the Senate Majority Leader, a position he held until being elected vice president under John F. Kennedy in 1960. Johnson was an extraordinarily persuasive man, and in dealing with his fellow legislators, his methods were so direct and forceful that his political dealings became known as the “Johnson treatment.” He could be both charming and heavy-handed, but when he was determined to get votes for a bill he favored, he could exert relentless pressure in persuading colleagues to follow his lead.

Although the negotiations were carried out in private, considerable evidence exists that John Kennedy did not really want Johnson as his vice president, but since Johnson, as majority leader of the Senate, was the most powerful man in Washington in 1960, Kennedy and his aides felt that Johnson should be offered the job. They also counted on Johnson to deliver the electoral votes of his native Texas as well as other Southern states. The Kennedy team was apparently shocked when Johnson decided to accept the position. The vice presidency of the United States has been described in less than glowing terms by more than one occupant of the office, and there is no question that Lyndon Johnson was frustrated over his lack of meaningful responsibilities. President Kennedy made him overseer of the American space program, but that did not really satisfy Johnson’s longing to be in the center of political action in Washington.

The vice president accompanied President Kennedy on his fateful trip to Texas in 1963. Shortly after Kennedy was pronounced dead at Dallas’s Parkland Hospital following his assassination, Johnson was sworn in aboard Air Force One, as President Kennedy’s widow, Jacqueline, stood by in her bloodied pink suit.

The vice president accompanied President Kennedy on his fateful trip to Texas in 1963. Shortly after Kennedy was pronounced dead at Dallas’s Parkland Hospital following his assassination, Johnson was sworn in aboard Air Force One, as President Kennedy’s widow, Jacqueline, stood by in her bloodied pink suit.

The transition from the Kennedy to the Johnson administration was understandably wrenching, first of all because Kennedy’s cabinet and staff were in a state of shock following the sudden death of their leader. In addition, John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson were about as far apart as two politicians of the same party could get in style and personality. Kennedy, the wealthy scion of an old Boston political family and Harvard graduate, epitomized everything glamorous and attractive about Washington politics. Mrs. Kennedy conducted herself with enormous dignity during the ceremonies following her husband’s death. Pictures of her standing side-by-side with her two young children, her son John being too young to comprehend what was happening, deeply touched the American people.

Lyndon Johnson, by contrast, had come from humble beginnings, He attended Southwest Texas State Teachers College and, after teaching for a year, worked his way up through the political ranks by his own means. Whereas the Kennedys suggested candlelit tables with fine glassware and china, Lyndon Johnson and his family conveyed the image of a rousing Texas barbecue. Johnson moved slowly and carefully during the weeks and months following Kennedy’s death, looking forward to the election of 1964 as he renewed contacts with political colleagues in Congress and elsewhere. As president, with the full apparatus of the White House at his disposal, he commanded attention and demanded loyalty.

Johnson’s forte was not foreign affairs, but the Cold War was a continuing reality, and the situation in Vietnam following the assassination of Premier Diem was murky at best; he could not afford to ignore the realities of international events. Johnson’s interests, however, lay in his dreams for domestic programs, as he planned an all-out assault on what he saw as America’s social skills: racism, poverty, lack of opportunity, and a host of other issues first addressed by Franklin Roosevelt during the New Deal. Johnson later told biographers that his goal had been to dance with the lady he called the “Great Society,” but instead he was distracted by what he called that “bitch goddess of Vietnam.” Although his legislative achievements in pursuing his goals for domestic improvements were stunning, in the end his legacy was determined by the Vietnam War. (See separate section on Vietnam.)

High on President Johnson’s agenda was progress in the area of civil rights, something which President Kennedy had started, but which was still far from completion upon his death. As a Southerner Johnson was in a strong position to push civil rights legislation. Though it took all his powers of persuasion, Johnson’s achievements in civil rights were of major significance.

Lyndon Johnson was one of the most powerful politicians in the nation’s history. He could be cajoling, pleading, bargaining, threatening, or promising, sometimes, it seemed, all in the course of the same conversation. He was famous for what was known as the “Johnson Treatment.” He was a man not to be crossed with impunity. Although he was unfailingly gracious to Jacqueline Kennedy following JFK’s assassination, the “Kennedy crowd,”or “Irish Mafia,” often left him feeling frustrated and angry. While he kept major Kennedy advisors such as Defense Secretary McNamara and Secretary of State Dean Rusk, he often clashed with JFK’s brother Robert, especially when the former attorney general began to challenge his Vietnam policy.

Lyndon Johnson was one of the most powerful politicians in the nation’s history. He could be cajoling, pleading, bargaining, threatening, or promising, sometimes, it seemed, all in the course of the same conversation. He was famous for what was known as the “Johnson Treatment.” He was a man not to be crossed with impunity. Although he was unfailingly gracious to Jacqueline Kennedy following JFK’s assassination, the “Kennedy crowd,”or “Irish Mafia,” often left him feeling frustrated and angry. While he kept major Kennedy advisors such as Defense Secretary McNamara and Secretary of State Dean Rusk, he often clashed with JFK’s brother Robert, especially when the former attorney general began to challenge his Vietnam policy.

The first task President Johnson faced in the civil rights arena was getting passage of the civil rights bill introduced by President Kennedy in 1963. Johnson spent most of his time early in 1964 working to get Congress to pass the bill. The House passed the bill by a comfortable margin, but it faced an uphill fight in the Senate. Johnson was aware that Southern Senators would lead a filibuster against the bill, and a vote of two thirds of the Senate was required to end it. Johnson kept a list of where every member of the Senate stood on the issue, and pulled out all the stops in an effort to persuade his former Senate colleagues to come around. The filibuster lasted three months, the longest one in Senate history, but eventually the bill passed.

As discussed in the Civil Rights section, above, two more major civil rights bills were passed during Johnson’s term: the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Civil Rights Act of 1968. All three acts reflect Lyndon Johnson’s sincere commitment to racial equality. As a Texan, he had seen racial discrimination up close and detested its effects on blacks and Mexicans. As a Congressman and Senator, he had worked hard to see that minorities were fairly treated under federal economic policies. His achievements in this area provide a stark contrast to his unfortunate policy in Vietnam. (See Civil Rights section.)

Additional Achievements of Lyndon Johnson included bills to establish the Medicare and Medicaid programs; the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964; creation of the Job Corps, a sort of domestic Peace Corps; the Elementary and Secondary Education Act; and the Head Start program. Johnson also sponsored legislation that revised immigration policies, toughened anti-crime systems, and sought to improve public housing and clean up urban slums and the environment at large. Although many of these programs failed to meet their objectives, it was the greatest reform movement since the early days of FDR’s New Deal. Lyndon Johnson presided over much of the “the sixties,” however, and the times were indeed a-changing.

America Goes to the Moon. Having launched the country on a quest to put an American on the moon by 1970, President Kennedy committed the nation to exploration of the heavens. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration mobilized the American scientific and engineering communities in a remarkable program to realize Kennedy’s vision. The seven Mercury astronauts made flights in the early 1960s, and then the Gemini and Apollo programs began to prepare for an eventual lunar landing. With the assistance of former German V-weapon rocket scientists and an aviation industry with much talent, the Apollo program moved forward smartly as NASA administrators kept a close eye on Soviet developments. In July 1969 the U.S. space program reached Kennedy’s goal: Astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the moon. With millions listening, Neil Armstrong announced, “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.”

The Apollo achievement was remarkable in that virtually every piece of equipment used for the flight had to be created from scratch. The challenges were large; three astronauts died in a fire early in the program, and three more nearly perished when the Apollo 13 spacecraft was damaged in an internal explosion. NASA eventually oversaw six landings on the moon, the last of which took place on December 11, 1972. Since then all space flights have been limited to low orbits. The Space Shuttle program, which followed Apollo, accomplished much but was plagued by accidents. The Challenger shuttle was destroyed during a launch in 1986, and the Columbia was destroyed during re-entry to the Earth’s atmosphere in 2003.

NASA eventually oversaw six landings on the moon, the last one on December 11, 1972. Since then all space flights have been limited to low orbits. The Space Shuttle program, which followed Apollo, accomplished much but was plagued by accidents, as the Challenger shuttle was destroyed during a launch in 1986, and the Columbia was destroyed during re-entry to the Earth’s atmosphere in 2003. NASA plans to retire the remaining shuttle craft in 2010 and replace them with a new vehicle, the Orion, designed to take astronauts back to the moon and perhaps beyond by the year 2020.

Although the manned spaceflight programs have received most of the public attention, unmanned satellites have made enormous strides in advancing communications, meteorology and discoveries about the origins and nature of the universe. Many products now in use in everyday life and in fields such as medicine are products of the space program. Everything from Velcro to heart monitors had its origins in the quest to explore the heavens. The Hubbell telescope has provided scientists with detailed pictures of distant galaxies and start systems.

See Tom Wolfe, The Right Stuff and the film of the same title; Norman Mailer, Of A Fire on the Moon; Also dramatic and historically sound are the Tom Hanks film Apollo 13 and his HBO series, From the Earth to the Moon. The NASA site is one of the most popular and frequently visited on the World Wide Web.

The 1960s: America in Revolt

The decade of the 1960s began chronologically in January 1961, a month that saw John F. Kennedy inaugurated as president of the United States. Kennedy’s inaugural address was highlighted by the memorable call to arms, “And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.” In those early days of the Kennedy administration the world seemed relatively calm. Still, the shooting down of the U-2 aircraft over Russia, the continuing threat of nuclear war, and the Cold War environment kept people on edge. The Bay of Pigs fiasco, the erection of the Berlin wall, the Cuban missile crisis and Kennedy’s confrontations with Khrushchev added to the tension that people felt, but the storm had not yet struck. Issues in French Indochina, rioting in the streets, and all the turmoil that has come to characterize the 60s was hardly a whisper on the horizon.

The sixties really began on November 22, 1963, when President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, by Lee Harvey Oswald. Young and vibrant, with a lovely wife and two small children, the President was extremely popular among young Americans. With his untimely death the nation began a descent into one of the most chaotic decades in American history. Lyndon Johnson, Kennedy’s successor, was a powerful President who achieved a great deal of what Kennedy had intended, and much more. His “Great Society” even went a step or two beyond the New Deal in terms of fundamental reform, but lingering doubts over Kennedy’s death remained alive.

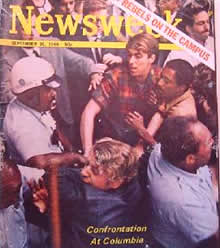

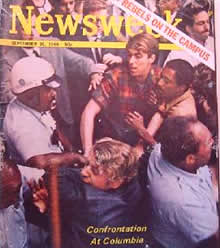

While the fifties were a “laid back” decade, the 1960s were in many ways the opposite. Whereas in the 1950s a popular television program proclaimed that “Father Knows Best,” by the end of the 1960s young people had convinced themselves that father did not know much of anything. Beginning with the “free speech” movement at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1964, a series of rebellions spread from campus to campus. The issues included such matters as women’s rights, the Vietnam War, and the nature of the university itself. Although in retrospect people think of those rebellions in terms of the “anti-war” movement, the student protests were much wider in their scope. In fact, Vietnam protests comprised only a minority of campus disturbances, many of which were directed at societal problems in general.

The more strongly the police reacted, the more rebellious the students became, and the larger their numbers grew. Across the nation, at hundreds of campuses, buildings were damaged or even destroyed, offices were ransacked, and professors unsympathetic to the students demands were driven from classrooms. In many cases the university was obliged simply to shut down. Following the invasion of Cambodia in 1970, hundreds of campuses were shut down because of student protests.

The more strongly the police reacted, the more rebellious the students became, and the larger their numbers grew. Across the nation, at hundreds of campuses, buildings were damaged or even destroyed, offices were ransacked, and professors unsympathetic to the students demands were driven from classrooms. In many cases the university was obliged simply to shut down. Following the invasion of Cambodia in 1970, hundreds of campuses were shut down because of student protests.

While cynics may have noted that the level of student protest seemed to rise the closer it got to exam time, the students were often addressing serious issues in a thoughtful manner. On the other hand, many leaders of the student movement—men and women whose names became well known beyond their own campuses—had fairly obvious political agendas; they sometimes seemed to be exploiting the rebellious conditions for their own purposes. The Students for a Democratic Society, SDS, had chapters on many campuses and often orchestrated demonstrations and other disruptive activities. (The organization still exists.)

While often high-minded, the student demonstrations were frequently violent, and they triggered responses from university officials that ranged from acquiescence, to forcible resistance, to what many students perceived as outright oppression. When college police forces proved inadequate to handle the growing level of disruption, local police forces and even national guard troops were called in, with predictable results. Taunted by what they viewed as foul-mouthed, “spoiled brats” of the upper classes who shouted epithets such as “pigs,” and worse, at them, the police often reacted with violence of their own, and the riots often turned bloody, even deadly.

In the best sense, the students and their sympathizers were trying to bring about positive change in American society. They saw themselves as friends of the working classes, a voice for the oppressed, and many of them made positive contributions to the civil rights movement. In the South, black students led the sit-ins and freedom marches and were on the front line when things got rough, as they usually did. For most white students the Vietnam War, while not the only issue, was the biggest issue. Their feelings were probably complicated by the fact that as college students they were deferred from the draft. Draft eligible young man had to remain in good standing, however, and professors often went out of their way to see to it that they did by guaranteeing males with low draft number an A grade. The Vietnam protests also called attention to what many saw as an unholy alliance between universities and government—more particularly the military establishment. Weapons research, for example, was attacked by students who felt that such work was morally objectionable in a university setting. (President Eisenhower’s warning about the military-industrial complex was cited often by sixties students.)

President Johnson marked time until his overwhelming reelection over Barry Goldwater in 1964, and then all hell began to break loose. As American troops were sent to Vietnam in ever-increasing numbers, as the civil rights demonstrations grew ever more bloody and violent, and as protests seem to erupt almost on a daily basis, mostly on college campuses, the 60s turned into a time of turmoil and trouble. Although a few early campus rallies were held to support the troops, their days were numbered.

The focus of much unrest on the campuses often dealt with civil rights. For example, in the spring of 1968, Columbia University in New York City erupted in part over plans by the University to build a facility in a housing area in neighboring Harlem. Although the design had been hailed as progressive, it was later judged to be discriminatory, as local residents were o be permitted to use only part of the building. Students soon took over the college, occupied administration offices, and eventually caused the university authorities to call for the assistance of the New York City police. Although today, in the aftermath of September 11, policemen and firemen are generally viewed favorably by most Americans of all generations, during the 60s student protesters saw cops, whom the called “pigs,” as the enemy. During an uproar at Boston University, the Boston tactical police were called in and blood was shed as the students resisted the police. At the University of Maryland in College Park, a campus generally not known for political activism, students shut down the main traffic artery of U.S. Highway 1 during rush hour. Fire bombs directed at ROTC buildings, mass protests, break-ins at draft boards, and marches on the Pentagon became part of the culture of the 60s.

The year 1968 was the peak of the turmoil as violence broke out in Chicago during the Democratic national convention. The Chicago police under Mayor Daley carried out what came to be known as a “police riot.” Protesters threw rocks, chunks of concrete and bags of urine at police, and the police responded with force. Blood was shed by demonstrators and occasional innocent bystanders. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy were both assassinated in 1968; it seemed to many that the country had not only lost its moral compass, but was rapidly running amok. The year 1969 saw the inauguration of President Richard Nixon, and as he seemed to be working to try to end the war, the turmoil also seemed to abate for a year.

The year 1968 was the peak of the turmoil as violence broke out in Chicago during the Democratic national convention. The Chicago police under Mayor Daley carried out what came to be known as a “police riot.” Protesters threw rocks, chunks of concrete and bags of urine at police, and the police responded with force. Blood was shed by demonstrators and occasional innocent bystanders. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy were both assassinated in 1968; it seemed to many that the country had not only lost its moral compass, but was rapidly running amok. The year 1969 saw the inauguration of President Richard Nixon, and as he seemed to be working to try to end the war, the turmoil also seemed to abate for a year.

In 1970 President Nixon authorized an invasion of Cambodia in 1970 to attack communist sanctuaries, four students were shot by National Guard troops at Kent State University in Ohio, and the protests erupted anew. Then came the confusing and frustrating end of the American involvement in Vietnam, followed closely by the growing Watergate scandal, and it seemed that once again, things were as bad as ever. (See The Nixon Years section.)

In 1973 the American POWs came back from Vietnam, Senator John McCain among them, and the escalating Watergate crisis led to Richard Nixon’s resignation in August of 1974. Although South Vietnam fell to the Communists in 1975, and the city of Saigon was renamed Ho Chi Minh City, most Americans viewed it from a distance. In 1976 the country rallied from its despondency in order to celebrate the bicentennial of American independence, and it seemed that by then the 60s were well over. But the nation did not go back to the way it had been in the 1950s—too much had changed. Civil rights legislation opened doors that had been closed for a century. Women had begun to assert themselves and move into areas previously unheard of for the “gentle sex.” Coed dormitories were common on college campuses, thus indicating that the sexual revolution had been, in effect, rubber stamped by university authorities. If parents were distressed, there wasn’t much they could do about it; and, in fact, they had lived through the 60s themselves and had been changed by the experience, as had all Americans.

The outcomes are hard to assess. The Vietnam War did come to an end, and substantial progress was made in civil rights and other areas. Perhaps those changes would have come about anyway, maybe more slowly, but maybe without arousing as much resentment. One outcome is certain: the university was changed forever. In the 1950s the university stood in loco parentis—in the place of the parent, knowingly accepting the responsibility not only for students’ education, but for their moral behavior as well. Dormitories were segregated by sex, use of alcohol and drugs was at least officially frowned upon, and male students were allowed to visit females in their dormitories only under controlled conditions. Students were expected to behave in class, obey the college rules and the law, and generally to conduct themselves as ladies and gentlemen.

By 1966 or 1967 all that had begun to change. Although the memory of the student protests seems retroactively to have centered on the Vietnam War, the students were angry about many more things. The university was now obliged to recognize that its students were adults, that they had rights, and that it was not proper for college officials to dictate student lifestyles, no matter how well intentioned such guidance might have been.

Events:

- The Port Huron Statement: Students for a Democratic Society create an agenda.

- The 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago

- The Shootings at Kent State University

College students were not the only ones who rebelled in the 1960s. The civil rights movement raised the consciousness of women as well. When one views the long history of relationships between males and females in various cultures, it becomes immediately apparent that only in recent years has anything like true equality between men and women begun to emerge. Though advances for women in American society have been notable, many other cultures still lag behind. The history of women in Western society has provided innumerable examples of women who have achieved remarkable things, up to and including the running of entire nations, as was done by Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, Queen Elizabeth the Great of Great Britain, Catherine the Great of Russia, and many others. Those women are exceptional by almost any definition.

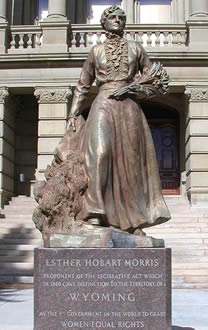

Many of you recall from early American history the Seneca Falls Convention organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and others in 1848. They stated in their declaration that “all men and women are created equal,” a radical notion in its time. From that juncture it took 70 years before women were granted the right to vote in the United States, although some states such as Wyoming, Utah and others afforded women the franchise well before the 19th amendment was passed.

|

Left: Alice Paul, President of the National Women’s Party, salutes the suffrage flag at the 75th Anniversary of the seneca Falls Convention in 1923. She wrote the text of the first Equal Rights Amendment and read it at that meeting. |  |

|

HBO Iron Jawed Angels Site. Alice Paul’s story is portrayed in the film Iron Jawed Angels, with Hillary Swank as Alice Paul. Link to Video Clip of Trailer (apologies for the commercial.) Link to the Women’s Rights National |

||

| Right: A statue of Esther Hobart Morris graces the front of the Wyoming State Capitol in Cheyenne. The inscription proudly procaims that Wyoming was “the first government in the world to grant women equal rights.” |

Alice Paul, pictured above left, was instrumental in the women’s suffrage movement. She and her colleagues worked tirelessly and courageously, even to enduring harsh treatment in prison, to get the 19th (Women’s Suffrage) Amendment passed. Part of her story is portrayed in the film Iron Jawed Angels, with Hillary Swank as Alice Paul.

Giving the women the right to vote, however, did not nearly make women equal in other respects. As late as the 1950s, as one can judge from old television programs, commercials, and newspaper and magazine advertising, women’s roles were decidedly different from those of men in the judgment of a majority of Americans. The appearance of Betty Friedan’s book, The Feminine Mystique, in 1963 began to change those perceptions, however. A few years after the book was published a group of women that included Catherine East (an alumna of Northern Virginia Community College) got together and formed the National Organization for Women. The modern feminist movement was underway.

The majority of Americans probably felt that opportunities for women ought to be expanded, and few could quarrel with the notion of equal pay for equal work, but the feminists had an uphill fight in achieving full equality. The best example of their difficulty is the fact that a constitutional women’s rights amendment, the Equal Rights Amendment, or ERA, although passed by Congress in 1972, was ratified by only 35 states, 3 short of the requisite 38.

Some objections to the equal rights amendment could were unconvincing. For example, some were concerned that privacy issues such as separate public restrooms might be negated by an equal rights amendment. Others argued that the Fourteenth Amendment, although it did not include women at the time it was passed, rendered the necessity of an equal rights amendment extraneous. Article 1 of the Amendment states:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Opponents of the equal rights amendment argued that women were indeed persons and citizens and therefore were fully protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. The National Organization for Women argued, on the other hand, that women’s equality needed to be made explicit. The most outspoken opponent of the ERA was conservative lawyer Phyllis Schafly. She argued that ratification of the amendment would mean that women would have to register for the military draft, and that they might lose Social Security benefits for wives and widows. Schafly has been credited with defeating the amendment.

The women’s rights movement has in any case had an enormous impact on opportunities for women. For example, in 1980 approximately 8% of practicing attorneys were women. Today the figure is close to 30%, but almost half of all students in law schools are women. A similar situation exists for women in medicine, where less than 30% of practicing physicians are female, but about half of all medical students are female. Women’s opportunities in the armed forces have expanded enormously, and women comprise well over half of all students in enrolled in colleges and universities. With the exception of the Roman Catholic Church, major religious denominations now regularly ordain women as priests or ministers.

The debate over the proper roles and functions of women is by no means over, however. Attempts to reintroduce an equal rights amendment have occurred, although the issue is clouded by recent debates over the issue of same sex marriages. Both men and women will continue to discuss and argue over the proper roles for females. Social relations between males and females are the product of thousands of years of evolution, and inborn genetic tendencies cannot be wiped out by social action or legislation. When I was teaching a course in Women in American History several years ago (100% of the students in the class were women) I asked the question, “If a boy and girl child were raised in a totally gender neutral environment, would they still gravitate towards traditional male and female roles?” The unanimous response of the class was that they would. Anecdotal evidence, to be sure, but nevertheless interesting.

Although the history of the women’s movement continues, one thing is clear: women in the year 2006 have far more to look forward to in terms of professional and other opportunities than women did in 1960. At that time most Ivy League colleges and the American service academies, Annapolis, West Point, and the Air Force Academy, were still male only. Women have indeed come a long way, but full equality remains to be achieved. They still face the dilemma of the necessity of dual incomes for a family to prosper, even as most women remain the primary caregivers to family members.

The Nixon Years

Richard Milhous Nixon was elected to Congress from California in 1946 and to the United States Senate in 1950. Selected as General Eisenhower’s vice presidential running mate in 1952, Nixon served eight years in that office and was narrowly defeated by John F. Kennedy for President in 1960. Nixon then ran for governor of California in 1962 and was defeated once again. In a bitter farewell to the media he proclaimed that, “You won’t have Richard Nixon to kick around anymore.” Nixon’s comeback, however, began when he made a rousing nomination speech for Barry Goldwater for president at the Republican National Convention in 1964.

Following Goldwater’s landslide defeat, Nixon worked quietly within the Republican Party and in 1968 was able to secure the nomination for president, running against incumbent Vice President Hubert Humphrey. Humphrey was saddled with Lyndon Johnson’s Vietnam War legacy, but the election was nevertheless very close. Former Governor George Wallace of Alabama created a diversion for frustrated Southern conservatives and carried five states in the Electoral College as he ran on the American Independent Party.

Richard Nixon campaigned on what he called a secret plan to end the Vietnam War, which was in fact nothing more than turning the conduct of the war over to the Vietnamese, in other words “Vietnamization.” He eventually got the United States out of Vietnam and achieved what he called “peace with honor.” (See Vietnam Section.) He and his national security adviser Henry Kissinger, who later became his Secretary of State, saw the Vietnam War as something of a sideshow to the larger issue of the Cold War tension between the United States and Russia and China.

Richard Nixon campaigned on what he called a secret plan to end the Vietnam War, which was in fact nothing more than turning the conduct of the war over to the Vietnamese, in other words “Vietnamization.” He eventually got the United States out of Vietnam and achieved what he called “peace with honor.” (See Vietnam Section.) He and his national security adviser Henry Kissinger, who later became his Secretary of State, saw the Vietnam War as something of a sideshow to the larger issue of the Cold War tension between the United States and Russia and China.

Pursuing a policy which they called “détente,” Kissinger and Nixon sought to reduce tensions among the three major powers. Nixon made a famous visit to Communist China in 1972, the first step in establishing formal diplomatic relations between the two nations. He also had a summit conference with Soviet Premier Aleksey Kosygin in 1972, at which various diplomatic agreements were reached. During his meeting with the Soviet Premier, President Nixon said in a toast, “We should recognize that great nuclear powers have a solemn responsibility to exercise restraint in any crisis, and to take positive action to avert direct confrontation.”

The U.S. entered several treaties with the two Communist nations during Nixon’s first term and supported China’s admission to the United Nations. A Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty was also signed in Moscow. Better relations between the U.S. and China and the Soviets may also have facilitated the end to America’s participation in the Vietnam War. Just after 1972 presidential election Kissinger signed a peace agreement with Le Duc Tho, the North Vietnamese negotiator. Whatever flaws Richard Nixon may have had, his foreign policy achievements have been considered notable. Although tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union remained high, neither side wanted a nuclear war. The consensus among both the American and Russian people was that Nixon’s policies had made the world safer.

Watergate. Like his predecessor, Richard Nixon was distracted by the Vietnam War. Well versed in foreign policy matters, Nixon made considerable progress in that area. He also streamlined many Great Society programs and attempted to shift the burden of and responsibility for much government action from the federal government to the states. As the Vietnam War seemed to be winding down in 1972, and Nixon’s “Vietnamization” program was bringing American fighting men home, Nixon was a strong bet for reelection, which he won by a huge landslide.

In June, 1972, a group of overzealous Republican underlings broke into the Democratic National Committee Headquarters in the Watergate office building in Washington in order to bug the phones and were caught and arrested. The actual events of the burglary had little if any impact on the election results, and if the incident had been handled swiftly and properly, the story almost surely would have gone away. Nixon’s staff, however, panicked and began what eventually became a massive cover-up of the “Watergate” events and their aftermath, and the President himself became deeply involved, even though he apparently had nothing to do with the break-in beforehand.

Two Washington Post reporters, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, who had covered the original break-in, stayed with the story even after it stopped being interesting. Following President Nixon’s landslide reelection and inauguration on January 20, 1973, the break-in offenders were found guilty and sentenced to jail terms. It was obvious to many, however, that the story did not end there. As additional White House staff members were found to have been involved in the process, the story began to grow. By June, 1973, the Senate had convened a special committee under the leadership of Senator Sam Ervin to investigate the Watergate charges and the White House involvement.