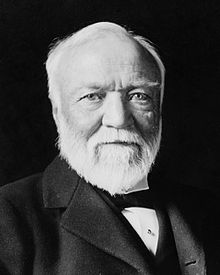

In the latter half of the 19th century, manifest destiny pushed America’s western borders further and further towards to the Pacific Coast, creating explosive demand for new railway lines. This westward expansion was largely made possible by the steel industry, along with the unwavering ambition, energy, and determination, of a visionary immigrant from Scotland named Andrew Carnegie. Andrew Carnegie’s vertical integration techniques, as well as his willingness to embrace new technology, allowed Carnegie to deliver low-cost, high quality steel, faster than any of his competitors. Carnegie’s obsession with reducing costs and controlling all aspects of production made him the wealthiest man in the world by 1901. In the end, Carnegie’s steel would be used to build thousands of miles of railroad, the Brooklyn Bridge and Washington Monument leaving, behind a legacy of the self-made man, and American exceptionalism.

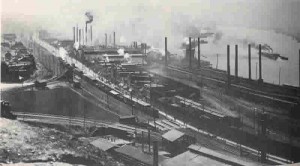

Carnegie, a Scottish Immigrant, landed in New York at the age of 12 in 1848. He found his first work in a textile mill cleaning bobbins for $1.20 a week. He later found work as a telegraph operator for Western Union. Carnegie understood from an early age, that one of the most important keys to success was social capital. He therefore set out to make an impression on every client he interacted with through Western Union. Carnegie’s strategy worked, as he managed to impress Tom Scott, a high-ranking official with the Pennsylvania Railroad who would hire Carnegie to be his personal assistant. During the Civil War, Scott gave the responsibility of managing war-time logistics to the young Carnegie giving him a true taste of responsibility, and the awesome power and capacity of the railroad system. It was also at this time that Tom Scott provided funds to Carnegie to invest in Wall Street, which he did so rather shrewdly, making himself a nice tidy sum. After the war, at the age of 29, Carnegie decided to turn his attention from managing logistics and wall street speculation, to reshaping the Iron and steel industry. As Carnegie put it “My preference was always manufacturing, I wished to make something tangible.” In 1872, Carnegie purchased 100 acres of land on the outskirts of Pittsburgh and formed Carnegie Steel. It was in this location where he would soon build the most advanced and efficient steel mill the world had ever seen.

Rapid Growth and Vertical Integration

Ever the shrewd businessman, Carnegie quickly embraced a new technology known as the Bessemer Proces in which steel was made from pig iron by burning out carbon and other impurities by means of a blast of air forced through the molten metal. The new process allowed Carnegie to produce better quality steel at a reduced price much more efficiently than his competitors. Within two decades of the formation of Carnegie Steel, Andrew Carnegie had succesfully increased the average weekly output of steel rails from 70 tons to 10,000 tons per week. The increase in capacity also reduced prices from $58 a ton to $25 a ton. All this efficiency however, took its toll on the average worker that labored 6 days of week, 12 hourse a day.

Ever the shrewd businessman, Carnegie quickly embraced a new technology known as the Bessemer Proces in which steel was made from pig iron by burning out carbon and other impurities by means of a blast of air forced through the molten metal. The new process allowed Carnegie to produce better quality steel at a reduced price much more efficiently than his competitors. Within two decades of the formation of Carnegie Steel, Andrew Carnegie had succesfully increased the average weekly output of steel rails from 70 tons to 10,000 tons per week. The increase in capacity also reduced prices from $58 a ton to $25 a ton. All this efficiency however, took its toll on the average worker that labored 6 days of week, 12 hourse a day.

Carnegie also realized that one key to improving profitability was taking ownership of the  entire supply chain. In other words Carnegie wanted to control all aspects of production, he not only wanted to refine the steel, he wanted to mine the raw ore, transport the raw materials, refine it in a mill, then produce a tangible product such as a steel rail that could be sold at market. Vertical integration, as it would be called, was a term first coined and implemented by Andrew Carnegie. As one observer noted, ““from the moment these crude stuffs were dug out of the earth until they flowed in a stream of liquid steel in the ladles, there was never a price, profit, or royalty paid to any outsider.” Carnegies aggressive cost cutting tactics troubled many industrialists who found it nearly impossible to compete. Rather than attempt to compete with Carnegie, J.P. Morgan decided to offer the aging Carnegie a buyout. Carnegie ended up selling his business to J.P. Morgan for $480 million making him the wealthiest man in the World. J.P. Morgan would later merge Carnegie Steel with companies he already owned to form U.S. Steel.

entire supply chain. In other words Carnegie wanted to control all aspects of production, he not only wanted to refine the steel, he wanted to mine the raw ore, transport the raw materials, refine it in a mill, then produce a tangible product such as a steel rail that could be sold at market. Vertical integration, as it would be called, was a term first coined and implemented by Andrew Carnegie. As one observer noted, ““from the moment these crude stuffs were dug out of the earth until they flowed in a stream of liquid steel in the ladles, there was never a price, profit, or royalty paid to any outsider.” Carnegies aggressive cost cutting tactics troubled many industrialists who found it nearly impossible to compete. Rather than attempt to compete with Carnegie, J.P. Morgan decided to offer the aging Carnegie a buyout. Carnegie ended up selling his business to J.P. Morgan for $480 million making him the wealthiest man in the World. J.P. Morgan would later merge Carnegie Steel with companies he already owned to form U.S. Steel.

Gospel of Wealth

Towards the end of his life, Carnegie turned towards philanthropy, famously stating “The man who dies rich…dies disgraced.” Over the course of his final years, Carnegie would give away upwards of $300 million of his own money building 2,500 public libraries. Carnegie created the famous “Gospel of Wealth” in which he boldly stated that it was the duty of the wealthy to oversee every aspect of their own philanthropy urging his fellow industrialists to, “administer surplus wealth for the good of the people.” Carnegie’s legacy will live on, in his vast body of philanthropic work, as well as the example of the self made man

http://www.biography.com/people/andrew-carnegie-9238756

Roark, James L., et al. The American Promise: A History of the United States, Vol. II: From 1877, 5th Ed.

Download this page in PDF format

Download this page in PDF format